By: Steven Abernathy

Neuroeconomics has gained attention in recent years. While it’s not exactly news, research continues to lift the veil on the mental processes behind people’s choices. Why would anyone, particularly a savvy investor, continually try to defy biases rooted within our neurobiology?

It’s unlikely it is for human beings to escape the predispositions of our complex brains. Inclined to see patterns where none exist, it is normal to make causal inferences. But this kind of thinking leads to faulty conclusions and biased decision-making.

This inclination toward Type 1 error does not serve us—it actually creates additional bias.

When examining one discount rate and translating value in the future to value in the present (and vice versa), the premise is standard economic theory. People are likely to employ a low discount rate over the long term; however, they employ a high discount rate in the short term. While it’s not entirely clear why this is the case, one hypothesis is that short and long term decisions are governed by different parts of the brain.

If the annual discount rate is 10%, that translates into $100 now – or $110 in a year. (While this doesn’t reflect actual consumer behavior, this idea, referred to as exponential discounting, is used in economic theory.) If one prefers to receive $10 today versus $11 next week, the implied annual discount rate is high. However, if the $11 is what’s given a year and a day from now and $10 in a year, the discount rate is substantially lower. The pattern of implied discount rates in the short term and low rates in the long term is hyperbolic discounting.

Based on the delay, researchers have found people often don’t go for the most advantageous option. When one chooses to begin collecting Social Security benefits illustrates the point well. The later payments begin, the higher they are. Yet, early eligibility in the U.S. begins at 62. A person may be poised to receive $1K per month at full retirement age and collect $750 if they opt to retire at 62. However, if they delay retirement until age 70, the payments jump to $1320. Yet, 40% of Americans begin claiming benefits at 62.

Melissa A. Z. Knoll and Anya Olsen’s article in the Social Security Bulletin examines this. Here again, different parts of the brain govern different decisions. As in our earlier example of a small but instant payout ($10 now vs. $11 later) the limbic structures were in control. It’s notable that this part of the brain is linked to addiction, dysfunction and impulsive behavior. However, when gratification is delayed, the prefrontal and parietal cortexes are active. Investors may choose to “trick” the brain in a variety of ways to avoid temptation.

And while humans prefer gains to losses, avoiding the pain of loss is our main goal. We have a greater aversion to losses than satisfied reaction to gains when the potential for analogous increases exists. In short, it is rooted in our neurology to forego a promising prospect in favor of staying “safe” and maintaining stasis. The possibility of feeling let down, the very idea of expectations not being met, unconsciously and automatically guides the decision-making process. Fear of loss looms large—our aim is not to experience it. This fear produces bias.

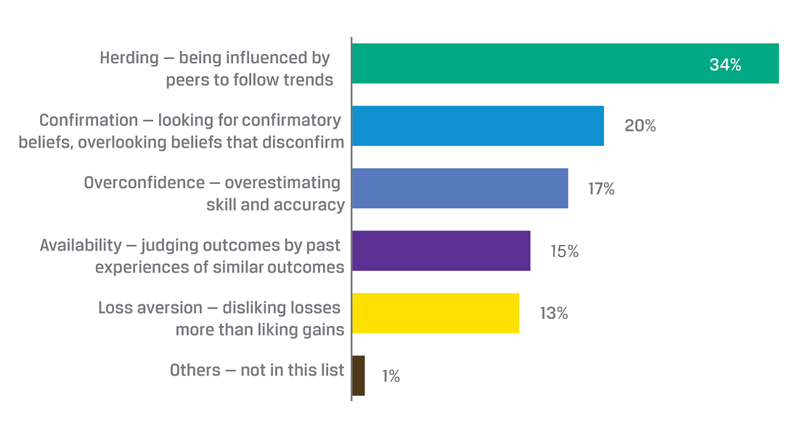

While the extent of loss aversion varies, it’s often predicated upon one’s recent personal experience. The Herding Mentality: Behavioral Finance and Investor Biases reviews the 2015 CFA Institute Survey. Data from their poll of 724 investors reveals the behavioral biases affecting investment decision making:

The poll’s top three finding are perhaps surprising. It found 34% of the 724 surveyed are influenced by peers to follow trends. When the herd is being influenced to follow trends, this can lead to inefficient market prices.

As Warren Buffett says, “Most people get interested in stocks when everyone else is. The time to get interested is when no one else is. You can’t buy what is popular and do well.” As the oft’ repeated quote indicates—social conformity unquestioningly affects perception. Yet, humans are largely driven by their need to be part of the crowd in spite of the facts that 1) research shows this is what people are inclined to do; 2) the herd is often wrong.

Confirmation bias, the inclination to seek out and incorporate data corroborating one’s idea while simultaneously neglecting contradictory evidence, was ranked as the 2nd most common bias.

Perhaps surprisingly, Overconfidence is at 17%. This low percentage might be indicative of a degree of pessimism or a sense of inadequacy when making decisions. In spite of the survey’s top findings: 1) the group can be wrong 2) ignoring or not factoring information that doesn’t support one’s investment occurs and 3) decision-making isn’t 100% objective, safeguards to reinforce where lay investors must proceed with caution are non-existent!

As we see from the examples above, social conformity is the norm. Independence can produce fear within the brain. Therefore people are inclined to think alike—even when the conclusions are wrong. A person’s ability to recognize the nuances of these biases—never mind manage them—is slim to none.

There are ways to mitigate the risk of your brain’s bias. Putting processes in place to manage your brain’s biases is one way. This involves a rigor of seeing investment decisions from every angle—a skill that takes years of training to hone. Individuals who remain independent show activity in a part of the brain associated with fear which is highly likely to lead to unnecessary losses. Hiring an objective facilitator before engaging in any investment decision is recommended to achieve a wise investment strategy over time as well as take the fear out of the equation.

Steven Abernathy is the co-founder and Chairman of The Abernathy Group II Family Office. Expert in shareholder rights. Applied the art of value investing to the Medical and IT sectors at Cowen & Co. Contributor to publications including Forbes, Barron’s, Wall Street Journal, Huffington Post, Private Air, The American Association of Individual Investors, Family Wealth Report, Medical Economics, Physicians Money Digest, Chiropractic Economics, Medscape, Practice Link, Practical Dermatology, Physicians Practice, Dental Practice Management, Buyside Magazine, The Bottom Line and more. Featured in Money Magazine.

Click here to view this article in the original magazine publication