Download a PDF version of this article

The Intelligent Investor Series: An Overview of Shareholder Activism and Value Creation Unrelated to General Market Returns

The capital markets are reasonably efficient and more often than not the market values assets accurately. Something must change for the price of an asset to depreciate or appreciate. When it’s the latter, the investor must be able to predict change. Shareholder Activism has a history of creating positive change. This paper explores how changes initiated by Activist investors create value far in excess of general market returns. The statistics show activists do this with significantly less risk than other forms of investment. In this paper, we will define the risks inherent in each stage of the Shareholder Activism process and how investors might profit from each.

What Is Shareholder Activism? Why Is It Important?

Summary

Once corporations came into existence, their unique structure allowed both core businesses and investors to profit. Left unchecked, however, conflicts inherent to a company’s structure may contribute to destroying shareholder value—but they do not have to. Today’s Shareholder Activists vigilantly assess the companies they target to unlock shareholder value.

Shareholder Activism involves risks, rewards, and the opportunity to invest with what S&P IQ calls the “Smart Money.” There is a clear “process” in a traditional Activist campaign. Many professional investors believe Activists are the smartest investors in the world, and they may transform the capital markets of the future.

Targets of Shareholder Activism may offer Intelligent Investors a fertile list of undervalued companies with a) a clear path to value creation and b) a high probability of success.

A Brief Overview of Corporate History

Rumor says the first corporations were established in Venice. Here, the first recorded history of human ingenuity combined with hard work, plus comingled investment capital, accomplished a common goal for a profit. Voilà—the first “corporation” was born. It differed significantly from the legal structures of today’s companies. However, this evolution created some negatives.

If someone had a wealth-creation idea yet lacked the capital to implement it, friends, acquaintances and neighbors could chip in to pool their capital thus buying (and owning) a percentage of the idea. Eventually one concept was so promising it commanded the attention of everyone in Venice. But it required a great deal more than one man’s capital.

This grand opportunity was the international spice trade—a venture which required a ship, a captain who knew how to get to India and back, a crew insane enough to risk their lives for the chance to earn their fortunes, and enough capital to fill the ship with spices, the world’s most precious commodity. Money was the most powerful component in business then, whereas labor was abundant and almost worthless. A group of families financed the trip. The ship returned home successfully, filled with a king’s ransom of spices which sold for an enormous profit. The ship’s captain, its crew, and the laborers were paid their wages and split their portion of the profits. After all borrowings were paid, the earnings were returned proportionally to the families who made the original investment. This method of raising capital to fund a specific venture eventually became known as a “società” or “corporation” in today’s terms.

Corporate Evolution

While this “corporate” structure evolved over centuries, one rule remained—those who put up the most money had the most influence in how the company operated. The process of raising money each time a profitable idea was embraced was labor intensive. Eventually, a more robust corporation supporting multiple endeavors eclipsed the societàs which supported only one project. Raising money for early corporations became a business. Investors found ways to convert their financial contributions into “debt” (bonds), and later into “equity,” (common stock). As methods of aggregating money became more sophisticated, money became more available. It also became less valuable.

Money became so available that expertise and competence became the true source of power. This shift transferred power from those with money to those who ran the company. This gradual shift from those providing capital to those who toiled inside the operating entity was a harbinger of what was to come. It shifted control from the owners of the company to those who ran it. When those with little to no ownership stake in a company are controlling it, their incentives change. They may become less concerned with creating value for shareholders and more interested in paying themselves generous salaries while enjoying executive perks.

Corporate Management Rules

This shift of power began the era of corporate management. Shareholders became disconnected from their investment as management found ways to exert more control. This ushered in a host of problems. Today, corporate management often acts as if they own the company. However, the law clearly states shareholders do. Management is merely an employee—the corporation’s Board of Directors governs management. The Board of Directors works for, and answers to the shareholders—the true owners of the company.

Management frequently manipulates control of the Board of Directors (Board) by populating it with friends and acquaintances. They are honored to become Board members, yet, afraid to voice objections due to fear of losing their position. A “rubber-stamp” Board could lead to a panoply of problems. Management may believe they are above the law, or they may award contracts to consulting companies they personally own. Management might also convince the hand-selected Board to allocate corporate funds towards their undeserved bonuses and ridiculous salaries. At times, management even creates legal structures, which entitle them to so much power that shareholders—the true owners of the company—have little say. In extreme cases, management actually absconds with shareholders’ money.

This is not always true of course. Honest, capable, and ethical management teams endeavor to create value for shareholders daily. But the trend towards management making decisions, which are not in shareholder’s best interests, continues. Typically, shareholders are not well versed about the companies they own, nor are they well informed enough to prevent or stop corporate corruption in the making. Most shareholders neither exercise the right to vote their shares nor read about the issues being voted on by the Board. Shareholders generally do not organize, nor do they have or seek access to management. As such, management is in a position to enrich themselves at the shareholders’ expense, while frequently owning very little of the company they govern. This is termed “moral hazardi”; however, at times, it seems more like “legal-theft.”

Since management’s ownership stake in the company they control is so small, their personal bottom line does not suffer when their decisions destroy value. Many are poised to hide behind the rules and regulations they created along with their (often) handpicked Corporate Board. A couple of poignant examples include the executive team at General Motors Corporation flying corporate jets to Washington on the day they declared bankruptcy, completely wiping out shareholders, and the CEOs of major banks and brokerage firms awarding themselves stratospheric bonuses as their banks failed in 2008 due to their mismanagement, eventually requiring tax-payer money to bail them out.

An Overview of Shareholder Activism and Why it’s Important for Investors

Shareholder Activism is the process of shareholders becoming actively involved in the governance and management of the companies they own.

While owning a minority of a company is typical, the goal of the Activist is to create value for all shareholders. Studies show shareholder activism produces returns that are more than double the overall market returns with much less riskii. Additionally, the correlation of the return is low enough to offer an intelligent diversification alternative for most investors, and qualifies as a satellite, for the “Core-Satellite” structure used by the wealthiest investors in the world.

Historical Perspective – Why Companies Fail

When companies fail due to lack of strategy, poor asset utilization, disruptive technologies, or simply poor management decisions, it takes experienced and engaged Board members, combined with well-informed, motivated, organized, and objective shareholders to step in and pull the companies out of their downturn.

Consumer behavior, and economic environments change. The laws of probability suggest current management, perhaps once well suited to guide their company through one specific economic environment, may not always adjust to demands of a constantly changing economic environment. Frequently a corporation’s Board recognizes the need for a change in management only in hindsight. The company struggles, revenues fall, profits evaporate, employees leave, and a once thriving organism turns into a decaying, vicious circle of negativity. As decay continues, the suffering shareholders are left to stop the slide and turn the company around.

Why does this happen so often? Isn’t management supposed to change strategy when the economy changes? Isn’t management supposed to anticipate change and put checks and balances in place which will allow the company to reduce risks and thrive in any environment? Simply put, “Yes.” Management is tasked with ensuring their company both thrives and delivers a solid shareholder return. But the ideal seldom occurs. When management does not have answers, someone needs to step in with new ideas and “out of the box” thinking to fix the corporation and restore shareholder value.

Biases, Tainted Decisions, and Who Is In Charge?

Management and the Board rarely have a purely objective perspective. Will management, receiving a million dollar-plus salary, along with incredible benefits, fire themselves? Will a Board member vote against a CEO’s value-destroying idea when s/he was asked by the CEO to serve on the Board?

Biases influence a Board’s decisions. Shareholders’ best interests are often ignored.

As companies evolve and adapt to an ever-changing competitive landscape, their challenges change. If the skill-set needed today, is not in-sync with the current environment, a problem is born and the management team must change.

This problem is likely to be structurally difficult to overcome. When a company’s challenges are outside of current management’s skill-set, there are typically three common scenarios: 1) management does not recognize there is a problem, or 2) management sees the problems, yet will not admit it, or 3) they see the problem and do not address it because a decision to change will cost them their job.

Intelligent Decision versus Self-Preservation

This sets up tension between the owners of the company (the shareholders), and current management. “Moral hazard” conflicts can displace good sense.

How common is it for a proud, long serving, C-level executive with a healthy ego to admit s/he is not up to the taskiii? Who, after a long parade of successes, readily recognizes—and admits—defeat? Who voluntarily abandons a multi-million dollar paycheck, prestige, and power to instead opt for no pay, potential disgrace, and loss of control? The company is often like a CEO’s alter ego which makes relinquishing his post willingly, next to impossible.

However if a leader cannot act as a fiduciary to make decisions in the company’s best interests, someone must. This is, in a healthy, well-run company, where the Board of Directors takes control.

While the company’s management is responsible for acting in the best interests of the company, the Board is responsible for acting in the best interests of the shareholders. Shareholders elect the Board–effectively retaining control over the Board—and eventually over management. This key distinction is often lost on investors.

The Problem with Shareholders as the Rightful Owners

While shareholders have the power to vote and effect change, most do not vote. Many feel they are not well informed enough to understand the operational or strategic problems facing the company. In essence, the shareholders (who vote to elect the Board, which is responsible for hiring and guiding management, who, in turn is responsible for running the day-to-day operations of the shareholders’ investment) are often not sophisticated enough, or engaged enough to render well-informed decisions in their own best interests. Thus, the “true-owners” are often absent and unable to govern their company.

Without Strategic Change Shareholders Lose

When consumers demand change, or a company’s operating model or product strategy is not in-sync with the buyer’s demands, the company spirals downward. The share price falls reflecting the absence of a bright future. Long-time shareholders become disheartened, give up, and sell shares, further depressing prices. Ultimately, the share price gets so low as to reflect possible bankruptcy and little to no value.

This is where Activists see an opportunity. They perform sophisticated analyses and can separate emotion from fact. It is the Activist who is likely to discover a gaping hole between current price and true value. When it is significant enough, and the problems causing the disparity can be fixed, a Shareholder Activist enters the picture.

Shareholder Activists – How They Do It

Shareholder Activists recognize the need for change and determine: how to fix what ails the company, how long it will take, and how much it will cost. First, activists devote their own money to the cause by purchasing a stake in the broken company. Buying a significant amount of shares in the open market shows current management they are serious. Next Activists recommend their strategy to current management and the Board. The intent is clear: fix problems and restore corporate competitiveness to create value for all shareholders. Activist shareholders are often the ultimate Value-Investors as their own money will go up first as proof of confidence in their own ability to fix the company. And no one is more motivated to roll up their sleeves and fix the troubled company than an investor with skin in the game.

How and Why Activists Create Value

The “fix” begins after Shareholder Activists invest and begin protecting that investment.

It is difficult work involving hundreds to thousands of hours of research, from top-notch financial analysts and industry experts who must first determine the difference between current price and true value. Then they must be able to define the actions needed to fix the problems, how long it will take, and how much it will cost. Then, they must be able to handicap the probability of success. In each segment of their analysis, they must be right.

When the Activists meet with management, they must be diplomatic in communicating their proposed solutions under potentially hostile conditions. They must be able to clearly show current management a more effective pathway to realize the corporation’s true value. And they need to be well versed enough in corporate governance law to wage a legal campaign against current management if, as is often the case, management says they are “not interested” in the shareholder proposals presented by the Activist. The legal costs for waging a campaign are born by the Activist. These costs often run into the hundreds of thousands to many millions of dollars for each campaign. It takes months to develop a strategy and figure out a method of communication management will embrace. All of this time and effort is born by the Lead Activistsiv who face enormous risk and a challenging road ahead. Few shareholders have this ability, but they exist. Unfortunately, Activists receive little credit for their success when the company’s operations improve and their share price dramatically increases.

In short, Shareholder Activism is an attempt by a few intelligent and skilled owners of the company, to improve the operations of their company. It would be ideal for the majority of shareholders to remain involved with, and engage the management of the company they own. Unfortunately, most shareholders are apathetic and let their investment fall into disrepair, nearing bankruptcy at times. Fortunately, the opportunity created for the clever, sophisticated investor to analyze problems and determine how to best fix a company often offers an interesting prospect.

How does Activism benefit the investing public?

Most investors will prosper for doing nothing other than remaining patient and supporting Activists while they take the actions needed to turn the company around. Interestingly, in this case, investors get “something” for doing “nothing.” Studies show that shareholders supporting activism receive approximately 15% per year in returns over and above the market’s returnsii. That is reason enough to take notice. However, when investors understand those returns have a low correlation to the market’s movements, the “value proposition” for remaining a supportive shareholder is almost unarguable.

What type of investor is best suited for this type of investing?

The ideal investor in an Activist’s campaign believes in the company’s business model and product line. The investor should be 100% convinced corporate assets offer significantly more value than the current share price indicates, and believes the Activist will implement actions to create positive change. Finally, the investor must remain patient as corporate change takes time, especially in situations where current management is fighting change. Below, we list a partial summary of investor characteristics which offer a good fit for Activism:

Value Investors – value-investors are often a “good fit.” They are capable of determining the difference between the “true-value” and current price. They generally make good partners for Activist investors, as they are familiar with investing in companies with problems, and are able to appreciate the company’s true value once fixed, while remaining patient during the company’s turn-around.

Event-Driven Investors – event-driven investors are a perfect fit, as there are always a series of events, or a changes, associated with the Activist’s campaign. The case for change and its timeline is typically outlined in the SEC filings by the Lead-Activists, making event-driven investors natural partners for Activist investors.

Contrarian Investors – contrarian investors also tend to make ideal candidates for investing in the Shareholder Activist’s target. Typically, the target of an Activist campaign is a company which has depreciated significantly over the last 3-5 years and has had significant turnover in the shareholder base. Contrarian investors tend to have the vision to determine what the corporate assets will be worth once the problems at the company are fixed. It often takes a large set of “contrarian investors” to support a successful Activist campaign.

What are the stages and the risks at each stage of Activism?

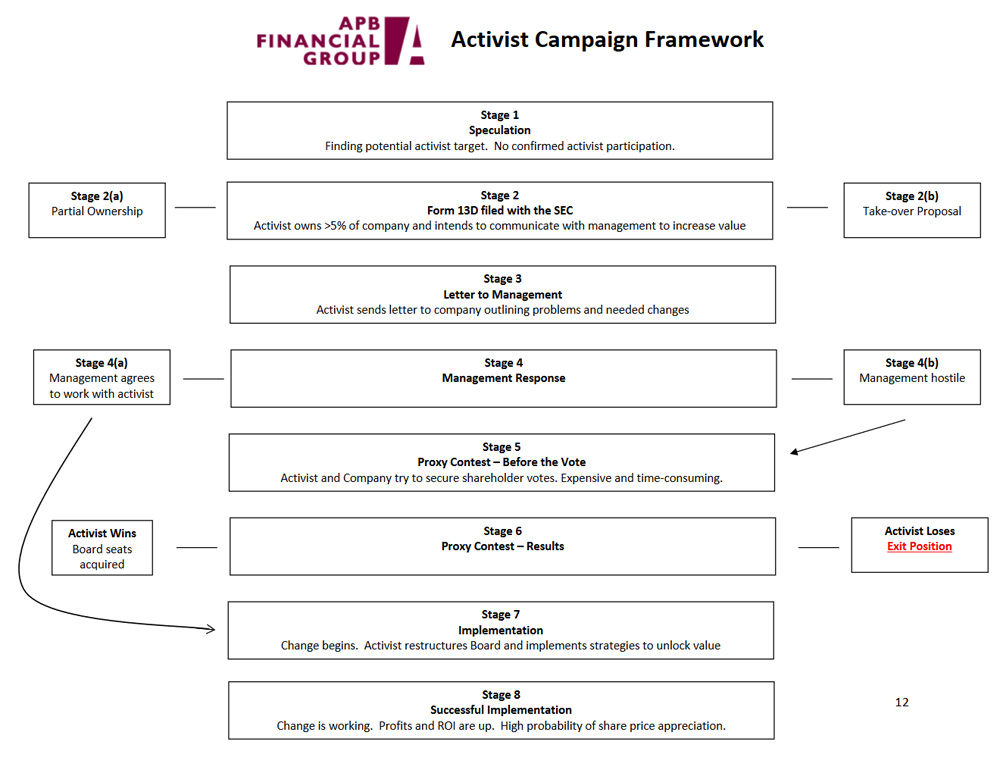

An Activist campaign has several stages of development. Below, you will find a framework for assessing the risks endemic to each stage of “Shareholder Activism.” Every investment is likely to offer twists, turns, and unintended consequences of actions, both good and bad; Activism is no different.

Below, you will find a step-by-step diagram describing a typical Activist campaign. Following the diagram, is a description of the action taking place at each stage of progress, and the change in investment risk.

Since controlling risk is the first order for every investor, we define 8 separate stages of risk. Each stage represents a change, and often a lowers the investor’s risk. For instance, using the example below, moving from Stage 4 to Stage 5 lowers the risk of the investment, as the Shareholder Activist has achieved a level of cooperation with current management.

Stage 1 – Speculation – Pre-Shareholder Activism – sets the stage for the possibility of an Activist target. This stage involves rigorous financial analysis without confirmed participation by any Activist yet. The difference between current price and true-value is identified. One variable-bad management-is usually involved is usually present, and is the most difficult variable for most investors to get over. The vast majority of investors will turn away once they have determined corporate management to be incompetent. Yet, this is the beacon of allure for most Activists. Investors at this early stage must realize there is no Activist activity so far. This stage is purely speculative.

Stage 2 – Form 13 D Filed with Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) – Activists owning 5% or more of a public company’s stock, and plan to influence management, must file Form 13D with the SEC. This is where the quest begins. The filing shareholder publicly declares their intention to actively communicate with management about measures they believe will increase shareholder value.

Stage 2(a) – Partial Ownership – is the most common type of Form 13D. The Activist states they would like to improve business operations. They may be planning to make suggestions to the Board and/or to management. Stage 2(a) is a low probability event. There is much to do and many hurdles for the Activist to clear. In order for the Activist to be successful at this level, a lot of things must go right. Despite the risks, many unsophisticated investors see this as an indicator of certain change. And while change may indeed be coming, it is far from assured here.

Stage 2(b) – Take-Over Proposal – infrequently, when filing a 13D with the SEC, an Activist may make an offer for the whole company. This is the most aggressive form of a 13D filing. Here, the Activist indicates they plan to speak with management about corporate improvements AND they would like to own the whole company outright. This has a slightly higher probability of success than a stage 2(a). However, this is still a low probability event until Activist ownership starts to approach the poison pill level, at which time the probability of success increases again. Note – there may be little change until the Activist makes a fully financed bid. If this happens, the investor’s risk decreases. This is still quite speculative. Management’s first reaction is to turn down the bid and get ready for an all-out war.

Stage 3 – Letter to management – the Activist’s campaign for change begins. Often the Activist sends a letter to the target company’s Board after meeting with management or the Board. In a majority of cases, the management and the Activist(s) have agreed to disagree on improvements which will create value for shareholders. The stage is set for an Activist campaign to begin. At this stage, it is expected to be a full-fledged fight, which often leads to a shareholder vote. This is costly and takes time. Stage 3 investing has a higher probability of success than a Stage 2(a). Yet there is still a low probability of investment success.

Stage 4 – Management Response – the company’s management team must respond to the Activist’s demands describing the most reasonable pathways to value creation. Suggestions for increasing corporate profitability are detailed and often considerably different from the company’s current operational business model. The Activists’ proposed solutions often call for streamlining the company, selling divisions that are unprofitable, and reallocating capital to stronger divisions with solid growth potential.

Stage 4(a) Initial Success – Great Outcome – a letter has been written to the management and communications have been exchanged. The management and the Activist (s) have agreed to work together. Stage 4(a) Activism means the Activists have avoided a costly and time intensive proxy contest. The campaign has a high probability of realizing the value-creating goals outlined in the Activist’s letter to the Board. Stage 4(a) offers a significant reduction in risk. However, management may stall, change their minds, or change their position 180 degrees. This will trigger a full-fledged proxy contest. Stage 4(a) Investing is a better bet than Stage 3 or 4(b).

Stage 4(b) Management says they have decided to reject the Activist’s proposed changes – in essence – “Thanks, but no thanks.” This stage defines the battle lines and sends a message to all current shareholders that the current management team is NOT planning to work constructively with the Activist.

Stage 5 Proxy Contest – Before the Vote – Communication has taken place. Management disagrees with the Activists partly or entirely. The campaign has evolved to the Activists believing they must change the current Board and/or management to enact value-creating strategies. In Stage 5, a proxy contest or shareholder vote is imminent. The Activist and management are vigorously engaged in securing shareholder votes. Corporate by-laws require the Activist to become well versed in the governance laws specific to the company’s state of incorporation which is expensive and time consuming. It also requires the Activist to become a politician of sorts, as the shareholders will vote to determine the company’s future. Stage 5 investors are no better off than Stage 3 investors.

Stage 6 – Successful Campaign/ Board Seats Acquired – in Stage 6, the Activist has gone through a Stage 5 challenge, and accomplished their goals of securing Board seats.

Stage 6(a) – If the Activist wins a minority of the Board seats, the investor is confronted with a difficult decision. Often, a minority Board representation is no guarantee that any of the Activist’s goals will be embraced as long as current management is in place. Management will often claim victory in this case. Make note however, when there is Activist representation on the Board, even if it is a minority, the Board meeting agendas often change, and depending upon the persuasiveness of the Activist, much needed change can take place. This is where intimate knowledge of the Activist’s history comes into play. The intelligent investor must know whether the Activist’s history includes convincing a majority of the old-line Board members to embrace what are often unpopular ideas to create shareholder value. And each investor must remember every Board is different and complex in its own way. If the Activist gains a minority representation on the Board, a significant amount of research is warranted to determine if remaining a shareholder is an intelligent decision.

Stage 6(b) – The Activist gains control of the Board (meaning the Activists assignees have a majority of seats on the Board), investment risk plummets, and the probability of success is significantly increased. This is most often an advantageous time for intelligent, risk averse investors to get involved.

* If, on the other hand, the Activists are defeated, meaning the shareholders voted to retain the current Board, we often advise investors to exit the investment as little to no change becomes the most likely outcome.

While there are many cases in which a proxy vote will initiate change, there are no assurances corporate change will take place. This is where knowing the Activist’s history is vitally important.

Stage 7 – Activist game plan implementation – Change Begins – in Stage 7, the Activist has removed or restructured the Board, owning either a majority (higher probability of success) or a minority of Board seats (indicating a lower probability of success). Now the implementation of change begins. This often includes new senior management, the hiring of an investment bank to consider value creating suggestions and share-repurchases as well as other actions. Stage 7 is represents a higher probability of success than Stage 6.

Stage 8 – Successful Implementation – the Change is working. Management change has taken place successfully, corporate ROIs are increasing, profits are up, and corporate assets or divisions are being bought and/or sold according to Activist’s campaign plans. When the Activist’s suggestions are implemented successfully, it indicates a high probability of share price appreciation. Stage 8 typically represents the highest level of probability that change will create value, yet may offer a low level of investment return to the shareholder, because lofty expectations have already been priced in.

What are the financial risks?

Investing alongside Activists can be simpler than traditional investing. The simplicity comes from knowing the Activist and clearly understanding the changes being proposed. While it is a certainty that no investor is right about their investment thesis 100% of the time, the fundamental framework for investing alongside Activists is much more transparent and easy to monitor.

Every “Intelligent Investor” wants 5 variables to be in place before an investment is made.

(a) They want to ensure the true value of the investment is significantly higher than the current price,

(b) They want a clear path toward value creation. The investor must truly understand how change will create value,

(c) They must be sure there is a high probability that change will take place,

(d) They want to be assured the Activist has a solid track record of success,

(e) They want the Activist, who is the lead investor, to have a significant amount of their own money in the investment – in other words, “Intelligent Investors” ensure those demanding change have skin in the game and as much, or more to lose than you do.

Every investment in a public security involves risks. Risks differ with every investment. While, the financial risks associated with investing alongside Activist investors are similar to most other equity type investments, there are several significant differences, which make Activism more attractive:

Less Downside – an investment in a security which is the subject of an Activist campaign often has the characteristics of a value-investment. This generally has less downside because hard assets, which could easily be sold, back the current price. Equally often, a value-investment may own a significant amount of cash and marketable securities.

There is usually less downside related to the equity or debt securities. Most often, the share price is lower than it has been over the last few years indicating general and widespread shareholder disapproval. Usually there is a problem at the company and room for significant improvement. After all, if a company was firing on all cylinders and running perfectly, it would not be cheap nor would there be much room for improvement.

More upside – while it seems counter-intuitive for an investment to have less risk and more reward, this is often true in the case of Activist investing. The secret is the (a) event-related change and, (b) the probability of the outcome. Since the company is damaged, the market believes the odds are higher than normal it will not be fixed. So current price is low relative to its true value.

When the market believes a company is broken and either cannot or will not be fixed, an opportunity exists for an intelligent and skilled Activist. Activists are confident they can change the company for the better and they put a significant amount of their own money, and reputation, behind the investment they make in the target company. This usually triggers share price appreciation. The possibility of a superior return is a function of the low current share price relative to the company’s true value. The larger the difference between current price and true value, the greater the upside potential.

Event-Related Share price movement lowers investment correlation – the success of investing with Activists largely depends on events and change initiated by the Activist investors. These events and changes often center around improving operational efficiency, a sale of underutilized assets, closing businesses that are losing money, or the intelligent addition of assets generally leading to a corporate turnaround. Will these changes create value and narrow the gap between current price and true value? There will be events or change(s) surrounding the target company. Be it an increase in share ownership, an offer to buy the whole company or management agreeing to adopt some—or all—of the Activist’s suggestions, change is likely.

What are the financial rewards?

The financial rewards for being involved in an Activist target are often substantial. Rest assured Activists rarely embrace the amount of work involved in this long and arduous process of corporate improvement unless a significant reward awaits them at the end of what is often a contentious tunnel. Recent studies clearly show that independent of market movement, on average, changes causing improvements in operating the business often translate into significant share-price appreciation which clearly outpaces the market’s returnsii.

What can happen along the way to thwart a campaign?

There are a great many things that can happen to thwart a campaign—including all the mistakes possible with any investment.

Risks include the Activist overvaluing the company, overestimating product demand and underestimating product obsolescence. Lack of management depth, implementing the wrong investment, or operating strategy, also offers hurdles to overcome. And there are many more. Every investor must take into account unpredictable macroeconomic events (in 2008, the vast majority of Activist campaigns were derailed as financing dried up when the financial world collapsed).

Activism involves change. Change involves risk. Turning around a company, rolling up similar companies, or selling divisions which seem to be superfluous or value destroying, involves risk. While these certainties exist, “Intelligent Investors” should never forget that Shareholder Activism risks are often lower than general market risk, as the Activist typically buys the asset closer to its “tangible book-value.” Many have termed this type of investing “Following the Smart Money.” Empirical evidence supports our belief that this statement is much closer to the truth than not.

What needs to happen for a campaign to work?

As you can see from the breakdown of the 8 stages of activism above, change is necessary in order for the Activist to create value. At any stage, though, the whole campaign can fall apart. When an Activist gets a significant amount of shareholders supporting their cause, the odds shift in favor of the Activist, thus increasing the probability of success.

In many cases, the Activist does not need to pursue a costly, time consuming, and highly emotional proxy contest (shareholder vote) as management understands they will lose the vote. Once management understands shareholders truly want change to protect and grow their investment, they often settle with the Activists, embrace change, and try to keep their jobs by going along with the Activists and shareholder’s demands for change.

Conclusion

Activist investors are often characterized by degrading terms, and are perceived as opportunists. They end up taking on difficult, dirty work overcompensated management couldn’t do. They are typically the target of emotional and incredibly personal assaults by management who has often spent shareholders’ hard-earned assets to protect their jobs, perks, and status. However, despite name-calling and negative comments by those opposed to change, Activists are likely to become recognized as saviors by investors who have lived through the value destruction endemic to most targets of Shareholder Activism.

The benefits of Activism are so obvious they may change the future of the Consulting Firm model. Companies unable to pull themselves out of a downward spiral may partner with Activists as opposed to hiring consulting firms such as Bain & Co or Accenture. The best Activists are turn-around specialists who not only isolate companies whose current price is far lower than true value, they perform the additional analysis to determine exactly what must be done to fix the company, how much it will cost, and how long it will take. Their own money is invested in buying a large stake in the company BEFORE they turn it around, thus aligning themselves with all other shareholders.

Corporate management may find working with Activists to fix problems at their firm a superior value proposition when compared to paying millions, to tens of millions in fees to a consulting company, which has no financial stake in their firm’s future. Activists could be offered a percentage of the firm’s profits realized from their efforts. This model of compensation is significantly better aligned with shareholder value creation than one in which management writes incredibly large checks to pay for advice lacking any shareholder alignment.

Activists also provide a level of rationalization required by capitalism. They isolate valuable companies in a state of disrepair. If the company is not fixed, thousands of dependent workers will lose their jobs. The herculean effort of turning around a struggling company may demand the application of new technology, the result of which may be fewer employees. Yet, fewer employees are better than no employees.

Shareholder Activism also offers a level of diversification as it allows participation in the equity markets, yet follows an appreciation path dominated by company-specific events, less related to the general market movements. It is often lower risk than the markets, offers the prospect of greater returns, and allows intelligent investors to simplify their investment process by standing on the shoulders of “Smart Money” with a vested interest in success.

What could be better than that?

i Moral Hazard is a situation in which a party is more likely to take risks because the losses will not be borne by the party taking the risk. In other words, it is a tendency to be more willing to take a risk, knowing that the potential losses will be borne by others.

Moral hazard may occur if a party that is insulated from risk has more information about its actions and intentions than the party paying for the negative consequences of the risk. Moral hazard most often occurs when the decision maker has a tendency or incentive to behave inappropriately from the perspective of the party with less information.

In our case, Management owns very little of the company yet receives money, not shares of the company, as payment for their services. This tends to incent Management to pay themselves regardless of the value they create, as they do not participate in the value destruction. Since, Management participates in decisions about whether to pay them more or less, and they most often choose “more”, it creates Moral Hazard.

ii “Follow the Smart Money” S&P Capital IQ, March 2013, Zhao, Pope and Wang http://bit.ly/1GXm2Ix

iii Corporate founders are the most frequent offenders here. The reasons are simple. Founding a company takes great imagination, creativity, enormous passion, and a single-mindedness that is almost maniacal to succeed. Managing a company demands that you listen to the buyers and users of your product. It demands change, and from time to time, it requires you to listen to market demands which are the polar opposite from Management’s views. This is incredibly difficult and at times impossible.

iv Keep in mind – management teams often become entrenched. They do not want to lose their job. Consequently, they choose to fight anyone trying to change the company management under the guise of “they know the company better than anyone else.” They will use shareholder’s money to fight the concerned shareholders. Never forget that management has more of an incentive to keep their job than to get the share price up. This creates an incentive for Shareholder Activists to try as best they can, to work in coordination with management, and not become hostile because hostile fights cost money, are emotionally draining, and distract the company’s management time from managing the company (if management is terrible and destroying value, that might be a good thing!).