By: Steven Abernathy and Brian Luster

Download a PDF version of this article

We estimate less than 1% of the general population knows what to ask before considering investing in a company. MarketWatch paraphrased Warren Buffett, “Put your money in index funds and move on… Seriously, you’ll do better. That’s what I plan to do with my own money once I am gone.” In short, buy index funds. Ample evidence proves the vast majority of investors would be considerably better off following this advice. Without unique knowledge, active investing is simply a guessing game.

Professional investors who achieve consistent success thoroughly assess every single company they buy, every single time. When the questions are answered completely, the analysis offers meaningful and often predictive data. There are no shortcuts, guessing, or gut-checking. When done right, these inquiries are likely to be an investor’s “Holy Grail.” But rarely are these questions asked—never mind answered.

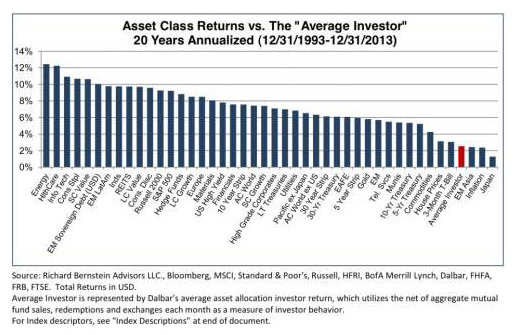

The chart below from Sam Ro’s article in Business Insider illustrates historical returns from virtually every investment category—and how poorly individual investors fared.

Before you start to say, “But this isn’t me.” Make note: individual investors make investments at high prices when the news is good, and sell investments at much lower prices when the news is bad. Actions are based on emotions not facts. Statistics show most professionals don’t fare much better.

The part-time investor’s quest is not unlike the amateur weekend flag football league player competing against a pro football team on Sunday—by himself. Successful wealth managers not only do rigorous analysis and evaluate a company from many angles, but, they focus 90% of their analysis on what could go wrong. Their livelihood depends on scouring for data that refutes their investment thesis and takes multiple factors into account. This is the antithesis of most part-time investors who focus the little research they actually have time for, on the positive or upside of their investment. Most investors (particularly non-professionals, though the professionals may be guilty of this too) don’t have an investment thesis. The few who only seek data supporting their thesis without considering other scenarios, or, seldom consider the source of their information which, if it isn’t “new”, was already considered and priced into their investment. It is surprisingly easy to ignore information not in support of one’s own ideas—and be unaware of it.

A wiser strategy is to take money planned for the investment, hire a professional, and acquire one of the Dimensional Funds world indexes. Hold it for 10+ years. This approach is in line with Buffett’s advice and is much more likely to increase net worth versus trying to compete with professional investors who can answer these questions—or derive a series of complex answers from their teams.

Why should an investor’s portfolio grow at less than the market’s return, simply because s/he was convinced spending two hours researching a specific stock based on one piece of data s/he found in a newspaper or magazine that the “herd” reads? To impulsively go forth rather than completing a full research analysis, which takes 100+ hours, is playing directly into the hands of the well-oiled financial propaganda machine. Remember, the only investment goal is increased net worth—that’s it. The following questions are likely to improve investment performance drastically. Aside from answering them, taking the time to ask is not standard investment operating procedure—and that leaves you open to greater risk. We recommend knowing…

1. What is the “real value” of the investment?

What does real value mean? This is often an answer found on the balance sheet for most companies. However, newer companies which require less property plant and equipment (PPE) might require a cash-flow based analysis. And still other companies require a combination of both balance-sheet and cash-flow based analysis. Determining “real value” is at times an art. It will establish the downside. If all other assumptions are incorrect, what is this investment worth in liquidation? If the company has assets which are worth $100M (current and long and short-term assets – current and long and short-term liabilities) and the current enterprise value (market value – cash + debt) is only $50M, it is likely that you are on to something and you should continue to answer the next question.

2. How much am I likely to lose if I am wrong?

If you lose your capital, you can’t invest. If there is no crystal-clear answer on losses, hold off on investing in the company and classify it in the “too hard to figure it out box” (THTFOB). If there is more information later that provides an obvious answer, re-evaluate.

3. Why is the investment undervalued?

Has the company been named in a $100M lawsuit? Is there asbestos litigation? Are there technological innovations which will render their core business obsolete? Could a public relations campaign contain the damage, or, reinvent the company’s reputation? No one can accurately predict future events. However, answering this question comprehensively will indicate if the company can be fixed—or not. Is there is a dramatic difference between the stock’s current price and its true value? It’s important to be able to explain that. Should an investor go against the opinion of the herd (and yes, the herd can be wrong), s/he must be certain about why s/he is going against the grain. Otherwise, this needs to go into the THTFOB.

4. What event will take place to realize the “true-value”?

In the vast majority of investment opportunities where the current price is below true value, some type of event must take place to bring the company’s current price back to true value. They could, for example: sell a money-losing division or increase operating efficiency, or introduce a new product. Something must happen to change the investment public’s mind about how to value the company. Knowing what the event is and when it will happen is critical.

5. What do I know that other investors don’t?

This is a tough one as it’s illegal to profit from non-public information. The vast majority of all public information is priced into the company’s current price. Is your information truly unique? If it’s not possible to state what you know that others do not, put the investment in the THTFOB.

Investors who achieve consistent success collect valuable, distinct information. They are also well-versed in finding as much data as possible to refute their investment thesis. The market is largely an efficient pricing mechanism. Without an informational advantage, it’s wisest to focus time on intelligent asset allocation. Investment performance in line with the markets translates into outperforming almost 90% of all other investors, including the professionals.

Outliers who manage to get it right again and again, like Carl Icahn, George Soros, and of course Warren Buffett, don’t have random methods. They have spent thousands of hours per year, for 30+ years, researching and discussing ideas with their networks. Buffett has been doing this for over 50 years with a single minded goal. Anyone who is employed and not able to spend over 1,000 hours annually on research is wise to check their ego and obtain a world index fund. However, for the people whose “luck” has led them to believe one or two years of positive investment results were not a coincidence, and, in 30 hours of research they could easily achieve what it takes skilled professionals 100+ hours to do, they (and you!) are free to choose “luck” as an investment strategy. On Wall Street, as in Las Vegas, the house always wins—and we recommend betting with the house rather than against it.

Steven Abernathy and Brian Luster co-founded The Abernathy Group II Family Office which counsels affluent families on multi-generational asset protection, wealth management, and estate and tax planning strategies. It is independent, employee-owned, and governed by an Advisory Board comprised of thought-leading business and medical professionals. Abernathy and Luster are regular contributors to several publications and blogs.

Click here to view this article in the original magazine publication